1. INTRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF CORROSION IN METAL CONTAINERS

Corrosion is technically defined as the slow destruction of a metal by the action of an external agent, resulting in a chemical or physical-chemical attack. Although metals are usually stable elements, the intervention of external agents breaks this equilibrium. In the context of metal packaging, mainly tinplate, this phenomenon is critical for product integrity and food safety.

All metals are in contact with the air, composed of 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. Since nitrogen is an inert gas, the aggressive action of the atmosphere on metals falls almost exclusively on oxygen. However, for the corrosive process to be triggered and progress, oxygen requires collaborators:

- Heat: Which, together with atmospheric oxygen, produces surface oxidation.

- Humidity: Which, in combination with oxygen, produces corrosion itself.

2. ELECTROCHEMICAL FUNDAMENTALS AND THE GALVANIC COUPLE

To understand corrosion in packaging, it is imperative to understand the electrochemical behavior of metals. Metals are classified according to their electrical potential:

- Anodic: Metals with negative potential that tend to release electrons and oxidize easily.

- Cathodic: Metals with positive potential (such as noble metals) that attract positive ions and are resistant to corrosion.

When two different metals are connected or come into contact in the presence of an electrolyte, a Galvanic Couple is formed. In this situation, the metal with the lowest potential (the most anodic) is the one that oxidizes.

2.1. The Specific Case of Tinplate (Iron and Tin)

Tinplate exhibits a fascinating dual behavior depending on whether the exposure is internal (without oxygen) or external (with oxygen).

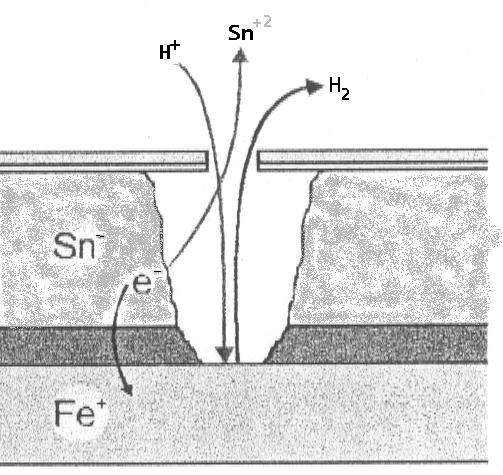

A) Inside the container (Absence of oxygen): Tin (Sn) acts as an anode against iron (Fe).

- Reaction: Sn⁰ ⇔ Sn⁺² + 2e⁻ (E₀ = -0.13 V).

- Iron: Fe⁰ ⇔ Fe⁺² + 2e⁻ (E₀ = -0.44 V).

- Tin oxidizes, protecting the iron. This phenomenon implies detinning, but maintains the structural integrity of the base steel.

B) On the outside of the container (Presence of oxygen): A polarity reversal occurs. Iron behaves as an anode and oxidizes against tin, which acts as a cathode.

- Iron, being more electronegative in this environment, suffers corrosion.

- This leads to the formation of iron oxides and hydroxides (the well-known “rust”), whose color varies from yellow to orange depending on the hydration.

The chemical reactions of iron oxidation are: Fe → Fe²⁺ + 2e⁻ (from metal to ferrous ion) Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺ + e⁻ (from ferrous to ferric ion)

In the presence of ambient humidity, the final product is hydrated ferric oxide of orange-red color: 2 Fe₂O₃ + 6H₂O → 4 Fe(OH)₃

3. CLASSIFICATION OF CORROSION TYPES

Corrosion can be classified into three broad categories according to the external agent that initiates it.

3.1. Electrochemical Corrosion It is the most common in metals exposed to humid atmospheres or submerged in water. It is governed by the galvanic series mentioned above. A classic example is the behavior of iron against zinc or tin:

- Against Zinc (Zn= -0.763 V), iron (Fe= -0.440 V) is protected because zinc is more anodic.

- Against Tin (Sn= -0.135 V), iron is attacked.

The presence of salts, such as sodium chloride (NaCl), accelerates this process according to the reaction: 2 ClNa + 2 H₂O ↔ 2 HCl + 2 NaOH The salt reacts but is not destroyed, contributing to continue the corrosion process as long as there is metal and humidity.

3.2. Chemical Corrosion Produced by the direct attack of acids and alkalis.

- Acids: Iron is attacked by non-oxidizing acids. The presence of sulfur is particularly dangerous, forming iron sulfide and acting as a catalyst, which makes the use of sulfurizing compounds in packaging risky.

- Alkalis: Attack metals such as aluminum and tin. Tin forms soluble sodium stannites, which dissolves the protective layer until total destruction of the coating.

3.3. Microbiological Corrosion It is one of the least known but highly destructive forms. It is produced by the action of:

- Anaerobic bacteria: Generate corrosive metabolites.

- Aerobic bacteria: Produce corrosive mineral acids.

- Fungi: Originate metabolic organic acids.

The metabolism of these microorganisms generates gases (CO₂, H₂, N₂) and substances such as ammonia, hydrogen peroxide and sulfides, creating a highly aggressive microenvironment for the packaging.

4. PROPAGATION AND MORPHOLOGY: LOCALIZED CORROSION

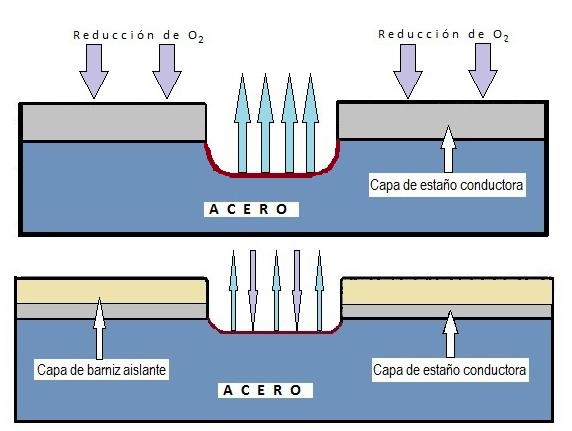

Although uniform corrosion exists (which affects the entire surface), this is rare in coated containers. The most common form in tinplate is localized corrosion, which attacks specific areas leaving others intact, generally due to failures or porosity in the coating (varnish or tin).

There are several types of localized corrosion of particular relevance:

4.1. Intergranular Corrosion Affects the union of the grains in the crystalline structure of the metal, weakening its mechanical resistance and causing irregular breaks. It is not the most common in packaging.

4.2. Crevice Corrosion Occurs in interstices or hidden areas where small volumes of corrosive solutions (salts or acids) are stagnant. It is typical in the closures of containers or under the easy-open rings.

4.3. Filiform Corrosion This is a superficial variation that occurs under non-conductive coatings (varnishes). It is characterized by forming narrow filaments (0.05 to 3 mm wide) that meander under the varnish.

- Mechanism: It works by differential aeration. The “head” of the filament is the anodic zone (where corrosion starts and there is acidification) and the “tail” is the most aerated zone.

- Factors: Requires a relative humidity greater than 60% and the presence of salts (chlorides) as initiators.

- Prevention: The quality or quantity of varnish does not prevent its formation; the key is to keep the humidity low and avoid saline residues.

4.4. Pitting Corrosion It is the most common and dangerous form of localized corrosion. It originates in imperfections or poorly aerated areas (under deposits). Its danger lies in that it perforates the metal in depth, sometimes being almost invisible to the naked eye from the outside. Pits can adopt various morphologies (narrow and deep, elliptical, in galleries, etc.).

4.5. Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) Implies a fragile fracture of the metal due to the combination of three simultaneous factors:

- Tensile stress (stress).

- A specific corrosive medium.

- A susceptible metal.

The process has two stages: the formation of an initial crack and its propagation until the fracture of the material. It is common to observe this in areas of deep drawing or in the rivets of easy-open lids.

4.6. Hydrogen Damage Caused by the diffusion of hydrogen in the metal, often accelerated by sulfurized ions from the decomposition of proteins (thioproteins) in the food. Basic reaction: 2 H⁺ + 2 e⁻ → H₂↑

5. FACTORS OF THE MANUFACTURING AND PACKAGING PROCESS

External corrosion is not only a material problem, but a process problem. Multiple stages influence the susceptibility of the packaging:

5.1. Mechanical Damage and Filling

- Feeding lines: Rubbing and shocks damage the exterior varnish, exposing the base steel.

- Closure: The adjustment of the seamers is critical. Poorly greased rollers or misadjusted mandrels can damage the coating in the closure area.

- Filling: Product residues on the container contaminate the sterilization water, increasing its aggressiveness.

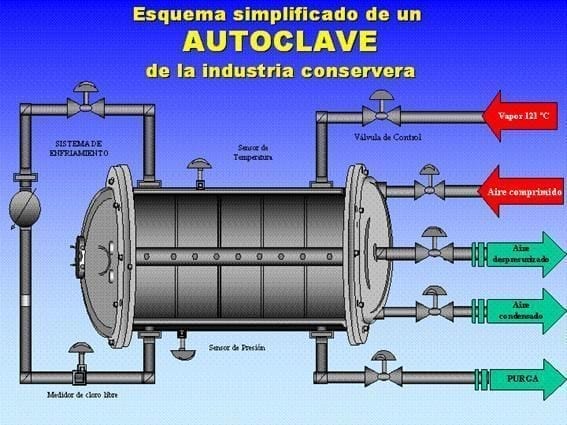

5.2. Sterilization and Cooling During the heat treatment in autoclave:

- It is advisable to use separators between layers to avoid hot rubbing.

- The air used for the counterpressure provides corrosive oxygen.

- The direct introduction of steam can drag alkaline condensates from the boilers that attack the varnish.

- Drying: It is essential that the final temperature of the container allows “self-drying”. The remaining moisture in the lid tray or under the ring is a breeding ground for galvanic cells.

6. WATER QUALITY: A DETERMINING FACTOR

The process water (sterilization and cooling) can be corrosive or encrusting. Key parameters to control:

- pH: Acidic or very alkaline media attack metal and varnish. Ideal range: 6.5 – 8.5.

- Conductivity: High values (< 2000 µS/cm recommended) favor the flow of current in galvanic cells.

- Chlorides and Sulfates: Must be kept below 25 mg/l.

- Dry Residue (TDS): Less than 500 mg/l.

6.1. Water Evaluation Indices Specific indices are used to predict the behavior of water:

A) Langelier Saturation Index (LSI): Evaluates the calcium carbonate balance. Formula: LSI = pH – pHs

- A negative LSI (< -0.4) indicates corrosive water.

- A positive LSI (> 0.2) indicates encrusting water (precipitating).

B) Ryznar Stability Index (RSI): Formula: RSI = 2(pHs) – pH

- Values >> 7 or 8 indicate high corrosivity.

- Values << 6 indicate a tendency to scaling.

Scales (white carbonate stains) are not only an aesthetic problem; they act as moisture retention areas, favoring subsequent corrosion.

6.2. Passivation Treatments To mitigate the aggressiveness of the water, cathodic inhibitors (passivators) based on zinc and phosphoric acid are added. These create a surface phosphatation on the steel that protects it. It is vital to control the dose, as an excess increases the conductivity and, paradoxically, the aggressiveness of the water.

7. STORAGE AND TRANSPORT: ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL

Once manufactured and processed, the packaging remains at risk. External corrosion during storage and transport is usually due to condensation and the presence of hygroscopic salts.

7.1. Warehouse Conditions

- Relative Humidity (RH): Must be kept low (below 60% to avoid filiform corrosion).

- Temperature: Avoid sudden changes that lead to the dew point and condensation.

- Salinity: Salt deposits attract moisture from the environment (hygroscopicity), initiating corrosion.

- Packaging materials: Cardboard and separators are not inert; they must be analyzed to ensure that they do not contain aggressive salts. The use of continuous plastic can be counterproductive if it retains internal moisture.

7.2. The Phenomenon of Condensation (Dew Point) The risk of condensation depends on the relationship between temperature and relative humidity. If the temperature drops suddenly, the excess vapor condenses into liquid water on the cold containers.

Critical examples of temperature drop allowed before condensation (for initial air at 35ºC):

- At 20% RH: The temperature must drop 28ºC (down to 7ºC) to condense (Low risk).

- At 50% RH: It is enough to drop 12ºC (down to 23ºC).

- At 75% RH: With only a 5ºC drop (down to 30ºC) condensation occurs (Very high risk).

This is critical in maritime transport, where containers undergo large thermal variations.

7.3. UV Protection Ultraviolet radiation (solar or from fluorescent tubes in insect killers) degrades varnishes and lithographs, weakening the outer protective barrier.

8. PROTECTION METHODS AND CONCLUSION

The fight against corrosion is based on prevention. The fundamental strategies include:

- Maintain the integrity of the varnish: A broken varnish concentrates the anodic attack.

- Eliminate hygroscopic residues: Thorough cleaning of the containers after closing.

- Absolute drying: Avoid water in crevices (closures, rings).

- Environmental control: Dry, ventilated warehouses with temperature control to avoid the dew point.

- Use of inhibitors: Chemical treatment of process water (passivation).

In conclusion, corrosion in metal packaging is a multifactorial phenomenon involving chemistry, metallurgy and atmospheric physics, whose control depends on the integral management of the entire life cycle of the packaging.