Everyday myths are popular misconceptions that sometimes persist stubbornly, even though they were refuted long ago. One such myth is also found in the food sector: according to popular belief, fresh fruits and vegetables from retailers contain, in principle, more vitamins and minerals than canned fruits and vegetables. However, the opposite is often the case. A comparative analysis carried out by the Tentamus chelab food institute, commissioned by the consumer platform weissblech-kommt-weiter.de of thyssenkrupp Rasselstein, debunks this myth. The study found that fruits and vegetables packaged in tinplate food cans often contain more vitamins and minerals than the fresh variety.

In particular, the measured values of minerals and vitamins in canned tomatoes were systematically higher than in the fresh product. The basis of comparison was the recommended daily intake for adults by the German Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung e.V.) for a 200-gram serving. “Freshly harvested fruits and vegetables already lose durability and nutrients shortly after harvesting. In contrast, immediate packaging in airtight and light-opaque tinplate food cans, their secure closure, and subsequent heating of the contents protect sensitive vitamins and important secondary plant substances such as lycopene. The can also preserves the taste and makes the fruits and vegetables last much longer, which reduces food waste and improves meal planning,” explains Nicole Korb, Head of Product Communication at thyssenkrupp Rasselstein GmbH, the only tinplate manufacturer in Germany.

Canned vs. fresh: comparative analysis with clear results

The Tentamus chelab institute examined fresh and canned tomatoes. The tomatoes were prepared in a typical household manner and analyzed for their content of selected vitamins (A, B1, B6, C, folic acid) and minerals (potassium, magnesium, calcium). The content of lycopene, a secondary plant substance with an antioxidant effect, was also determined.

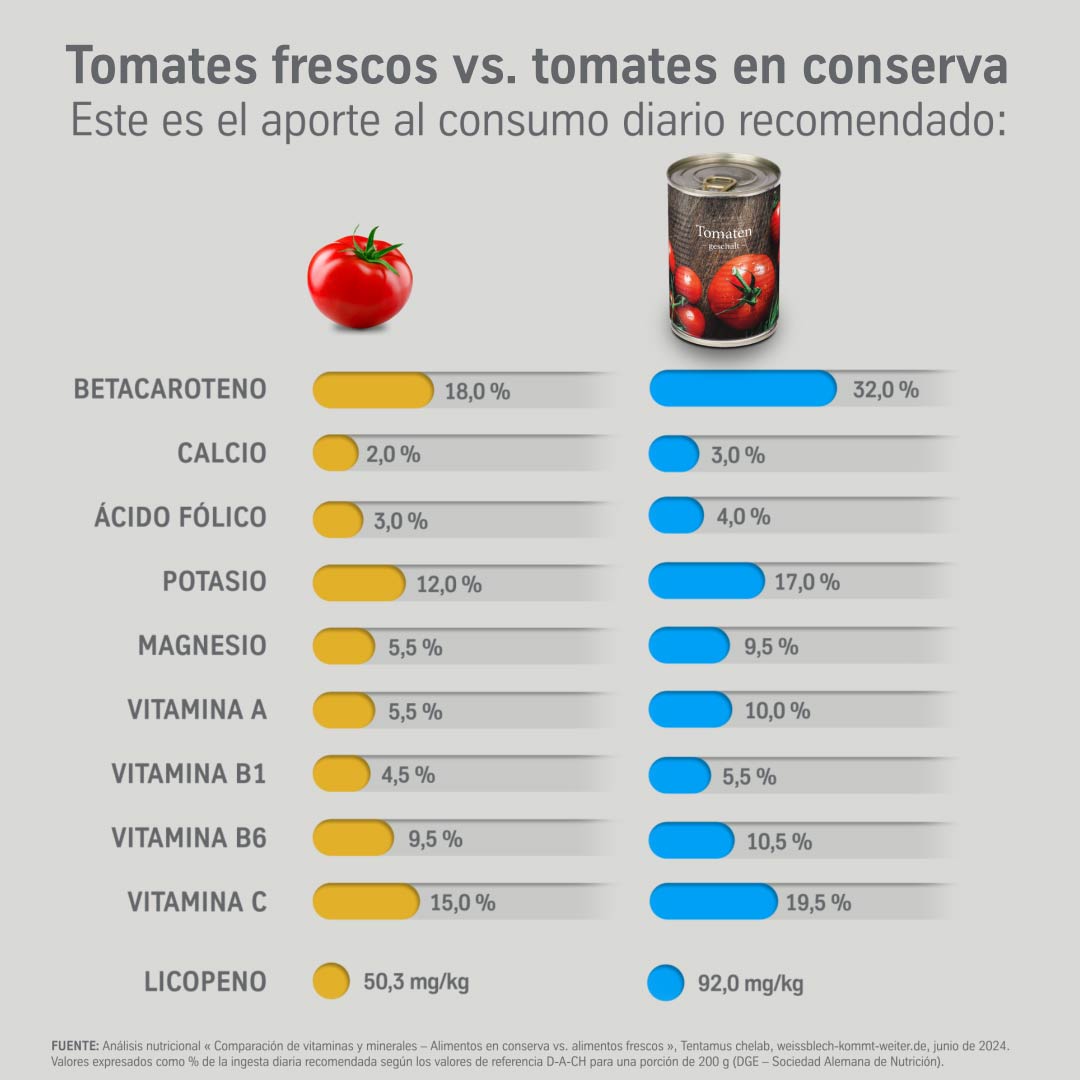

The result: canned tomatoes achieved significantly better results than the fresh variety. Magnesium and vitamin A reached an average of 10% of the recommended daily intake, while fresh tomatoes only provided about 5.5%. In the case of potassium and calcium, the values of canned tomatoes were approximately one-third higher (potassium: 17% vs. 12%, calcium: 3% vs. 2%), and for vitamin C and folic acid approximately one-quarter higher (vitamin C: 19.5% vs. 15%, folic acid: 4% vs. 3%). The proportions of vitamins B1 and B6 were slightly higher. Canned tomatoes were also far ahead in beta-carotene: they cover 32% of the daily requirement, while fresh tomatoes only reached an average of 18%.

The lycopene content in the tomatoes was also measured. This secondary plant substance has an antioxidant effect and helps protect the body’s cells from damage caused by so-called free radicals. Lycopene is also relatively heat-stable and fat-soluble. This means that it is preserved during heating and that its bioavailability even improves, i.e., the body can absorb it better. Compared to fresh tomatoes, canned tomatoes contained significantly higher amounts of bioavailable lycopene (92.0 vs. 50.3 mg/kg).

A stable supply of important nutrients even in winter

In principle, nutrient contents are subject to natural fluctuations, influenced by various factors such as the length of transport routes or the

seasonality of the products. The type of nutrient plays a decisive role here. “What is striking in all the samples is that the measured mineral values are systematically in the high range. These remain stable even after preservation,” explains Dr. Florian Birk, laboratory director at Tentamus chelab. “Unlike minerals, vitamins are continuously degraded over time, both in fresh and canned products.” An exception is vitamin C, which degrades, for example, on contact with air. As the cans are airtight, vitamin C is preserved longer until opening. In general, the degradation of vitamins is much slower in canned products than in fresh ones.

Another advantage of canned foods is their independence from seasonal, logistical, and climatic fluctuations. Especially outside the harvest season, in winter with low temperatures, or in regions with less access to fresh products, the food can guarantees a stable supply of essential nutrients. Thanks to the long shelf life of fruits and vegetables, food waste is also reduced. Meal preparation can be planned better, which means that much less food ends up in consumers’ garbage. Waste can also be significantly reduced in trade and catering through the use of canned products. “Many consumers know the advantages of the can thanks to everyday cooking: thanks to its round shape and smooth surface, no food remains in the tinplate packaging that should go into the pot. In addition, thanks to the easy-open ring, no utensils are needed to open the can, which saves even more time in the kitchen,” adds Nicole Korb.

Tinplate: optimal for the circular economy and automated processes

Unlike many other packaging materials, tinplate makes an important contribution to the circular economy. In fact, tinplate is almost completely recyclable and can be separated quickly and efficiently from other materials thanks to its magnetic properties. In addition, it can be recycled repeatedly without downcycling, i.e., without loss of quality. In the EU, 82% of all tinplate packaging is already recycled. The targets set by the new European Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) for 2030 have already been exceeded. Today, food packaging must not only offer exceptional recyclability and high-quality properties but also be particularly suitable for industrial processing. The food can allows for high efficiency in production, with average filling speeds of 500 units per minute. This speed, together with the robustness of the tinplate can, contributes to an economical production process. For food manufacturers, this is a decisive advantage, especially in standardized products such as fruits and vegetables.

About the comparative analysis:

The Tentamus chelab food institute in Hemmingen, near Hanover, carried out the analysis on behalf of weissblech-kommt-weiter.de, an initiative of thyssenkrupp Rasselstein. Both fresh and canned tomatoes were examined. All samples were prepared in a typical household manner, and the tomatoes were cooked or heated accordingly. Subsequently, the content of potassium, magnesium, calcium, vitamins A, B1, B6, C, and folic acid was measured. The lycopene content was also analyzed. The purchase and sampling took place in June 2024. The basis of comparison for the recommended daily intake was the D-A-CH (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) reference values of the German Nutrition Society for adults, with a daily intake of a 200-gram serving. When the recommended values differed between men and women (for vitamins and magnesium), the values were averaged.